What I learnt when my mother left.

The cons and pros of an unhappy childhood

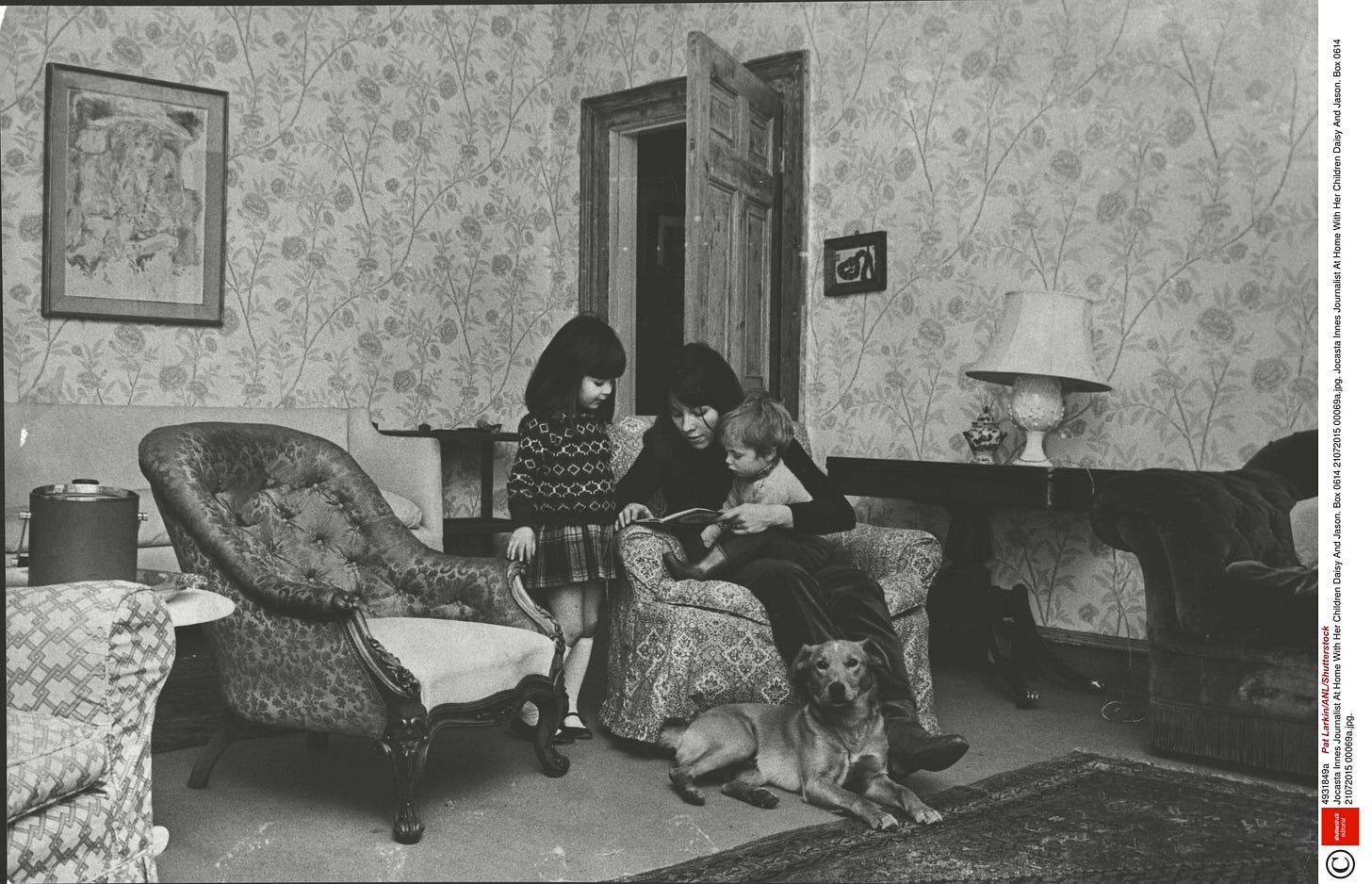

Dunmow, Essex, 1968. My brother and I are sitting in the back of my grandmother’s mini which is parked on the High Street. I am six and he is four. My grandmother who has short grey hair turns to my mother who is wearing an embroidered afghan coat that smells like wet dog and says, “ You’d better get it over with.” The windows of the car are misted up and I am drawing hearts on the condensation with my finger. My mother moves her body round to face us. She doesn’t know what to say. My grandmother fidgets with the car keys. At last my mother speaks. She tells us that she loves us very much, but she won’t be coming home to live with us and our father. She is going to live somewhere else, but we will see her all the time – every other weekend and half the holidays. It’s possible that I cried then, but I don’t remember that bit. My mother’s absence was just one of the many inexplicable things that happened when I was young. One moment I was living in a house in a Georgian square off the Old Kent Road, and the next my brother and I were living with my father’s mother in a cottage in the New Forest. We liked living in the New Forest: there were trees to climb, bicycles to ride, and a grandmother who liked playing Snap. Two years later my father came to visit us with a woman who he told us was going to be our stepmother. I asked her how she was and I calculated that she was seventeen years older than me. She was only just old enough to be my mother.

We went back to live with my father and my stepmother in London in a house with many stairs and strict rules. My stepmother was young but she was firm. Bedtime was at eight thirty, meals were a necessary evil, and shoes were always sensible. Nothing was left unregulated. My stepmother would make a list of all the clothes that we took on our trips to stay with my mother in Swanage and tape it to the inside of our suitcase. In her backward sloping cramped French handwriting she itemised the socks, the pants, the shorts, the cotton dresses that she had packed. On our return she would open the suitcase and her lips would compress into a very thin line as she emptied the jumble of single socks and dirty kinckers into the washing basket.

My mother didn’t have a washing machine then, she didn’t even have a telephone. We wore the same clothes every day and put ourselves to bed. In the morning we would have to wake up my mother and the man who was to become our stepfather if we wanted breakfast. We learnt how to make toast under the grill. In the summer we went to the beach every day, gazing enviously into the rows of beach huts with their flowered curtains and red enamel kettles. In the beach huts children our age were eating ham sandwiches with no crusts that came out of a Tupperware box. In my mother’s house there was bread that you had to cut yourself and blocks of cheese. The butter was always hard even though there was no fridge. Sometimes my mother would make chips and I still remember them as being the most delicious thing I had ever eaten. But I had to eat fast as my stepfather’s hand would suddenly dart onto my plate and take the particularly golden chip that I had been saving for last. He was not a man for deferred gratification. If he wanted something, he took it. This was the man that my mother had left her husband and two children for. They talked all the time about something called ‘Lorrenceandfrida’. Later I deciphered this to mean DH Lawrence and Frieda the woman he married after she left her husband and their two young children. My stepfather like Lawrence was a working class novelist from the North of England. He said the word book with a long vowel sound like the one in Moon. We thought it sounded funny, he told us that we sounded funny. He told us that ear wax was the best lip balm. When we tried putting ear wax on our flaking lips, he laughed so hard that sprays of saliva erupted from the corners of his mouth. Teasing two solemn children was his favourite thing to do. He knew that I had dreams of being an actress, and he devised a scenario to make me instantly famous. He would film me as I jumped off the cliff onto the rocks below. I didn’t like the sound of this, but he reassured me by saying that I probably wouldn’t die although I might be paralysed, but the suffering would be worth it. “ You will be first crippled film star in history. “ He recounted the fall and its aftermath with such glee that he made me cry. My mother who was laughing, told me not to be so silly. He’s just teasing you, she said. He doesn’t mean it. But I wasn‘t sure.

In my other house, my real house there was no teasing. When my stepmother said something she meant it. All of us, including my father, played by her rules. Because of her I always did my homework, practised the piano and learnt how to sew on buttons. In my mother’s house, my unreal house, I taught myself to use a corkscrew, put my two younger sisters to bed and roll a cigarette. My brother and I became very good at what is now called code switching . We operated like agents behind enemy lines, forever concealing our true identity.

It's a useful skill being able to slip between one world and another and pass in each. I learnt early, too early maybe, that everything – bedtimes, chocolate consumption, high heels, novels by Lawrence Durrell, elbows on the table, frosted blue eye shadow, was relative – what was forbidden in one house was positively encouraged in the other. When I was twelve my mother bought me a pair of red leather sling backs from BATA with two inches of stacked wooden heel. I knew that my stepmother would not approve of these shoes, she insisted on t bar sandals from Start Rite – so I used to smuggle them to school every day and put them on when I was there. But like all spies I grew over confident , my cover was blown when my stepmother came to pick me up from school and found me wearing the red shoes. In my memory she called me a painted hussy, but I know that is not true as my stepmother’s first language was French and although she was completely fluent it was not idiomatic. The shoes were confiscated. I never saw them again, although I can remember everything about them – the punched leather brogue like pattern on the upper, the narrow horizontal stripes on the stacked heel.

My divided childhood taught me how to lie, how to read the room, how to live a double life. All useful skills, it turned out, for a career in television. I was fluent in the language needed to assuage the insecurities of talent, or to dispel the fears of anxious contributors. I could say “ you will hardly notice us,” without blinking. I could sense the talent’s blood sugar dipping before they did and always carried treats in my pockets like a dog trainer.

I didn’t know what I didn’t know until I had a baby. For the first time in my life I felt unequivocal. I loved my infant daughter completely even at 4 am. I remember the glorious feeling of certainly when I realised that nothing, no Geordie D. H. Lawrence, would take me away from her. But with that certainty came the knowledge that my mother had not felt like that. Like Frieda von Richtofen she had chosen her lover over her children. Growing up I had accepted this, but when I became a mother myself I realised that her action had been a violent one. It tore a hole in my life and in hers.

I have no idea what sort of person I would be if my mother had stayed, but I do know that her leaving left me with a relentless need to prove myself. That can be a good thing : it means I work hard and I am never complacent, but it also means that nothing is ever enough. I remember a tutor at university telling me that childhood trauma was a blessing in disguise, “ If you survive the initial hurt, you will be invincible because you will be fearless, nothing can hurt you that much again.”

In some ways he was right – in some ways I am fearless. I have written my first play which is being produced this summer – I know it could end in failure but that hasn’t stopped me. But on the other hand it doesn’t take much – an unreturned phone call, a curt email – to send me into quagmire of self loathing. I will feel every word of a bad review like a brand on my skin, but I also feel that unless I keep making things I have no purpose.

I once met a journalist who wrote profiles for a national newspaper. He said that the first paragraph was always the same for a successful person: at some point in their early life they would have either lost a parent to death or divorce, had an illness , or faced some other kind of trauma. Learning early on that life is nasty brutish and short makes you determined to beat the odds. But it also means that it is difficult to enjoy anything because you know how easily it can be taken away. I have tried very hard to be the mother I didn’t have for my children: available, conscientious, aware. I am much closer to them than I was to my mother , but I wonder sometimes if my style of mothering is an improvement. I want to protect them from the pitfalls of life, even though I know that until they fall they won’t know what they are capable of. But I hope that whatever happens they know that they are loved.

Of course my mother was no more culpable than all the fathers that have walked away from their children. No one should be trapped in a marriage they don’t want to be part of. I don’t blame for her leaving, I simply wonder how she could have done it. I remember my brother who must have been about four clinging to her legs when she came to visit us once at my grandmother , and watching her peeling his hands away. The only time I have come close to this was leaving my oldest daughter at nursery school. I felt bereft even though I was due to pick her up three hours later. How my mother managed to walk away I will never know.

The one thing I do know is that my childhood has made me a writer. After smelling the hair of my children,I find my greatest satisfaction in ordering words on a page. I like the alchemy that turns my incoherent thoughts into something readable. As a child things happened to me, now I can make things happen even if only on the page. When I challenged my mother once about her leaving, she shrugged and said, “ But you turned out fine, didn’t you?” It’s not a question I can answer, but at least it has given me something to write about

.

That is very kind thank you.

Thank you for writing this. I'm sorry you went through that. I just wanted to say that my mum left when I was a child, and it's so unusual that it's a relief to see you write about it. The circumstances for me were different (my mum found it very, very hard to go, but I still felt rejected), but I know exactly what you mean about "code switching" between houses. It must've been awful to go back and forth between two such very different places, especially having two such very different step-parents (what was your stepdad thinking, joking about you jumping off a cliff? And how dare your stepmum confiscate shoes which your *mum* bought for you?).

As a child, depending on which house I was in, I behaved as if that other life, and those other people didn't exist. I noticed very early on that if I *did* mention them or that other existence, there was sudden awkwardness, and it made me itchy. I needed to avoid the awkwardness. So I just pretended and became a "people-pleaser" - I think, deep down, I wanted to avoid the risk of further rejection. I've had to work very hard at my rejection issues to deal with accepting criticism etc. Or not even criticism - someone pointing out a tiny mistake could potentially send me into a rage in the past.

I don't know if you felt this too, but I have a younger brother as well, and I often buried my feelings in order to protect him. I was behaving like a small adult. I retreated into my imagination so perhaps that's why I'm a writer? Perhaps my love of family history comes from putting the pieces together, not pulling them apart?

Do parents who create these situations ever realise what they're putting children through? I'm not saying people should stay in unhappy marriages, but once they've left, they need to ensure their children aren't silently terrified all the time. My GP's waiting room has a poster on the wall, among ones telling people to get vaccinated, and to see a doctor about persistent coughs saying, "Splitting up? Put your children first." It makes me sad for all the other children every time I see it.